Parents shielded children to prevent ‘negative attitudes’

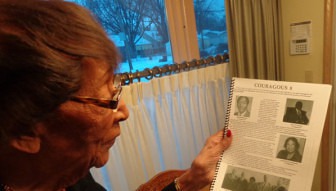

Dr. Hallie Hendrieth-Smith watched the movie Selma with keen interest. She grew up outside of Selma, Alabama, and once lived in the city as a young adult after her family bought a house there that they occupied for many years.

“One of the things I was proud to see,” said Smith after she and her husband were invited guests at a recent screening and post-film discussion of the hit movie in Edina, “[is] that they really included a lot of our people, [but] I was hoping they would have included the story of the [Montgomery] bus boycott. Movies are one thing, and history is another.

“My mother was one of the first [Black] persons allowed to vote in Selma after the Civil Rights [Act was passed in 1964],” said Smith proudly. Her brother Ulysses Blackmon worked with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as his secretary. “He was one of the eight people who took the State of Alabama to court.” She and Dr. Ralph Abernathy’s sister were college classmates as well.

“I was born in Orrville, Alabama,” continued Smith. “When I finished junior high school, my mother sent me to Bessemer [Ala.] to go to high school.” But after living for a time with a strict relative of her mother, Smith’s father came and brought his daughter back to Selma, where she lived with her mother’s nephew and finished high school. “I lived in Selma when I finished high school and college,” she recalled.

Her family owned a house in Selma since the 1940s until three years ago. She easily recalls the Jim Crow segregation laws that existed in her youth affecting every aspect of life in the South. “Even if [Blacks] sat in the back of the bus, if there were not enough seats for Whites, they would have to get up and move,” explained Smith. The boycott, which lasted over a year, was just the beginning of further protests to help dismantle segregation.

“Selma was so segregated. African Americans lived on one side of town and Whites on the other side of town. There were no public schools for African Americans. You were not permitted to eat at the same restaurant [as Whites]. You could not stay in the same hotels.”

She remembers the time a Black man was arrested for teaching Blacks how to vote. “Even when they were allowed to vote,” the votes weren’t counted, she said. Blacks mainly were employed as servants “and did all the work that was necessary to be done. It was very seldom to get a job other than for washing and ironing and cooking.”

Nonetheless, Blacks did get educated, said Smith. “All my teachers in Selma were African Americans. They had degrees.”

Although they were segregated times, Smith said her parents tried to shield her and her siblings from it. “My parents did not allow us to know all of that until we finished high school so we would be able to handle it. If we had been exposed to that at that time, we probably would have had a different attitude.

“My father was a farmer, and my mother was a musician. All my family were musicians. We had an attitude that we were important. They didn’t want us to have a negative attitude.”

For example, she and her family rarely took segregated public transportation. “We thought the buggy and the mule was a wonderful thing — that’s how we got to where we had to go.”

Smith chose education as a career. “When I finished high school, there were three or four of us that went down to get a certificate so we could teach. We taught only five months a year — the rest of the year we could go get our college degree.” She also worked as a dean of students at a private school.

While teaching she met her first husband, who was an ordained AME minister, and they got married. She later moved to Minneapolis, where her husband was assigned to build a church, and became a longtime educator as a teacher and principal in the Minneapolis school district.

Selma is an important movie for the present generation of Blacks to get a good look, albeit in dramatic fashion, at how things were back then, surmised Smith. “I would want them to know that inasmuch as those things happened, the opportunities they have now should be taken advantage of. So many young people didn’t have that privilege that they have today. When they go to school, they should place themselves in the position to do a good job, and to take advantage of the opportunities they have now.

“Instead of complaining, put that stuff behind,” she advised. “As my father used to say, those persons who practice that will [be] limited, and we cannot afford to be limited.”

Charles Hallman welcomes reader responses to challman@spokesman-recorder.com.