The Justice Department’s recent investigation of the Ferguson, Mo. Police Department not only revealed widespread racism in its operation, but described how poor Blacks were targeted to boost the sagging revenues of small municipalities.

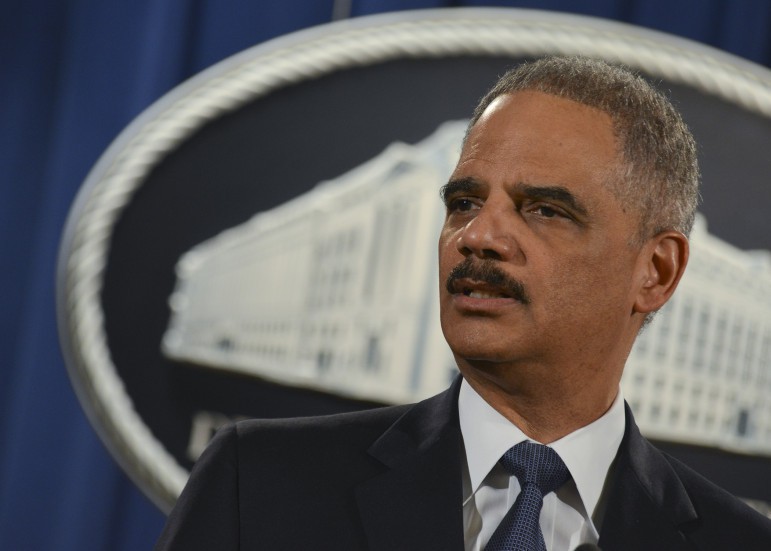

“Ferguson police officers issued nearly 50 percent more citations in the last year than they did in 2010 – an increase that has not been driven, or even accompanied, by a rise in crime,” Attorney General Eric H. Holder said at a press conference to release finding of its investigation of Ferguson. “Along with taxes and other revenue streams, in 2010, the city collected over $1.3 million in fines and fees collected by the court. For fiscal year 2015, Ferguson’s city budget anticipates fine revenues to exceed $3 million – more than double the total from just five years prior.”

Holder said that Ferguson police officers were pressured to deliver on those revenue goals, some even competed to see who could write the most citations in a single stop.

“Once the system is primed for maximizing revenue – starting with fines and fine- enforcement – the city relies on the police force to serve, essentially, as a collection agency for the municipal court rather than a law enforcement entity,” Holder explained.

He told the story of one woman, who received two parking tickets in 2007 for $152 and has paid more than $500 in fines and fees to Ferguson. She was arrested twice for failure to pay tickets and even spent time in jail and she still owes Ferguson $541.

Beyond the compounding fines and frequent traffic stops, Ferguson police, charged with upholding the law, ran roughshod all over it, routinely violated the civil rights of African American residents.

Holder said that the Justice Department’s investigation found “a community where deep distrust and hostility often characterized interactions between police and area residents.”

He said that the Justice Department’s investigation showed that Ferguson police officers “routinely violate the Fourth Amendment in stopping people without reasonable suspicion, arresting them without probable cause, and using unreasonable force against them. According to the Police Department’s own records, its officers frequently infringe on residents’ First Amendment rights.”

Holder added: “And even in cases where police encounters start off as constitutionally defensible, we found that they frequently and rapidly escalate – and end up blatantly and unnecessarily crossing the line.”

Holder recounted a 2012 arrest in which a Ferguson police officer approached a 32-year-old African American man while he sat in his car after playing basketball at a park.

“The car’s windows appeared to be more heavily tinted than Ferguson’s code allowed, so the officer did have legitimate grounds to question him,” said Holder. “But, with no apparent justification, the officer proceeded to accuse the man of being a pedophile. He prohibited the man from using his cell phone and ordered him out of his car for a pat-down search, even though he had no reason to suspect that the man was armed. And when the man objected – citing his constitutional rights – the police officer drew his service weapon, pointed it at the man’s head, and arrested him on eight different counts. The arrest caused the man to lose his job.”

These types of incidents were anything but isolated, according to Holder.

Even though Blacks account for 67 percent of the population in Ferguson, they comprised more than 85 percent of the traffic stops, between October 2012 and October 2014. Once they were stopped, Blacks were twice as likely to be searched than Whites, but 26 percent less likely to possess contraband or illegal substances.

Nearly 90 percent of the incidents where police officers used force involved Blacks, and in all 14 uses of force involving a canine bite in which the race of the person bitten was reported, the person was African American. Between October 2012 and July 2014.

“This deeply alarming statistic points to one of the most pernicious aspects of the conduct our investigation uncovered: that these policing practices disproportionately harm African American residents,” said Holder. “In fact, our review of the evidence found no alternative explanation for the disproportionate impact on African American residents other than implicit and explicit racial bias.”

Even though city officials and Ferguson Police Department (FPD) officers attributed the individual experiences of residents trapped in the maze of the municipal enforcement system to a lack of personal responsibility, they seemed to ignore the gaps in their own professional accountability to the system.

The Justice Department reported that, Ferguson police omitted critical information from the citations, making it impossible for a person to know what offense they are being charged for, “the amount of the fine owed, or whether a court appearance is required or some alternative method of payment is available,” the report said.

“In some cases, citations fail to indicate the offense charged altogether; in November 2013, for instance, court staff wrote FPD patrol to ‘see what [a] ticket was for’ because ‘it does not have a charge on it.’ In other cases, a ticket will indicate a charge, but omit other crucial information. For example, speeding tickets often fail to indicate the alleged speed observed, even though both the fine owed and whether a court appearance is mandatory depends upon the specific speed alleged.”

Not only did Ferguson police officers submit incomplete citations they also gave people the wrong dates and times for court appearances, increasing the likelihood that they would face additional fines for failing to appear at the correct time.

“It is often difficult for an individual who receives a municipal citation or summons in Ferguson to know how much is owed, where and how to pay the ticket, what the options for payment are, what rights the individual has, and what the consequences are for various actions or oversights,” said the report. “The initial information provided to people who are cited for violating Ferguson’s municipal code is often incomplete or inconsistent. Communication with municipal court defendants is haphazard and known by the court to be unreliable. And the court’s procedures and operations are ambiguous, are not written down, and are not transparent or even available to the public on the court’s website or elsewhere.”

The Justice Department recommended that Ferguson implement a robust system of community policing, prohibit the use of formal or informal ticketing and arrest quotas, and encourage de-escalation and the use of minimal force necessary. The department also recommended that police officers seek supervisory approval before issuing multiple citations and making arrests in certain cases.

In the wake of the report, two Ferguson police officers were forced to resign. The fate of Tom Jackson, the chief of police, is still uncertain.

Holder said that dialogue, by itself, will not be sufficient to address these issues, because concrete action is needed. However, initiating a broad, frank, and inclusive conversation is a necessary and productive first step.

“It is time for Ferguson’s leaders to take immediate, wholesale and structural corrective action,” Holder said. “Let me be clear: the United States Department of Justice reserves all its rights and abilities to force compliance and implement basic change.”

Thanks to Freddie Allen and the NNPA.org for sharing this story with us.