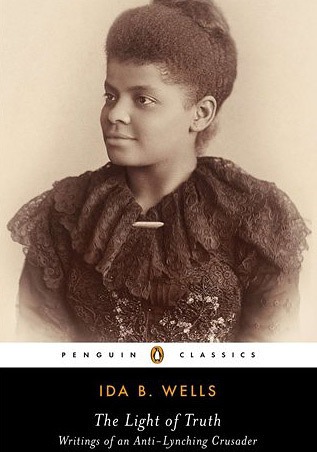

“Ida B. Wells was born a slave in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862. After beginning a teaching career to support her orphaned siblings, she moved to Memphis to become a journalist…

“Ida B. Wells was born a slave in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862. After beginning a teaching career to support her orphaned siblings, she moved to Memphis to become a journalist…

In 1883, she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a

train, an experience that she chronicled in her first published piece. Though Wells achieved success as a writer, editor and even co-owner of a newspaper, her greatest accomplishments came after the lynching of a close friend in 1892 spurred her into a lifelong anti-lynching campaign.

She published powerful diatribes against lynching, leading to death threats and forced exile in the North… Wells devoted the rest of her life to civil rights, publishing widely and delivering impassioned speeches.”

—Excerpted from the Introduction (page i)

Over 70 years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, Ida B. Wells was similarly arrested for refusing to surrender her seat on a train to a White person. Wells survived the ordeal and was eventually inspired to embark on an impressive career as an eloquent advocate on behalf of African American civil rights.

Her specific focus was lynching. The practice went unpunished for over a century during which not one White person was ever tried, convicted and executed for employing that brand of vigilante justice against any of the thousands and thousands of Black men, women and children.

Edited by Mia Bay and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Light of Truth: Writings of an Anti-Lynchings Crusaders (Penguin Classics, paperback, 624 pages) is a collection of Wells’ fiery essays culled from her early writings.

In a professional and persuasive journalist tone, Wells recounts case after case in which a rush to judgement led to a gross miscarriage of justice. For example, in Selma Alabama, a “colored man named Daniel Edwards” was hung from a tree and riddled with bullets as a “warning to all Negroes that are too intimate with White girls.” Truth be told, he had secretly dated the daughter of his employer for over a year until the scandalous relationship produced a biracial child.

Another entry discusses the details of the 1892 lynching in Quincy, Mississippi of five African Americans merely on suspicion of poisoning a Caucasian, despite their already having been declared innocent by the local coroner. In this instance, Wells chastises White Christian ministers for failing to give the matter “more than a passing comment” in the pulpit. She goes on to cite the slayings as “proof of the moral degradation of the people of Mississippi.” And so forth.

A debt of gratitude is owed Ida B. Wells for preserving for posterity, a host of illustrative examples of racist mobs bent on satiating their bloodlust by visiting violence on the bodies of Blacks in vile fashion, without any concern about guilt or innocence.